The Life of a Showgirl: Taylor Swift has made herself too big to fail

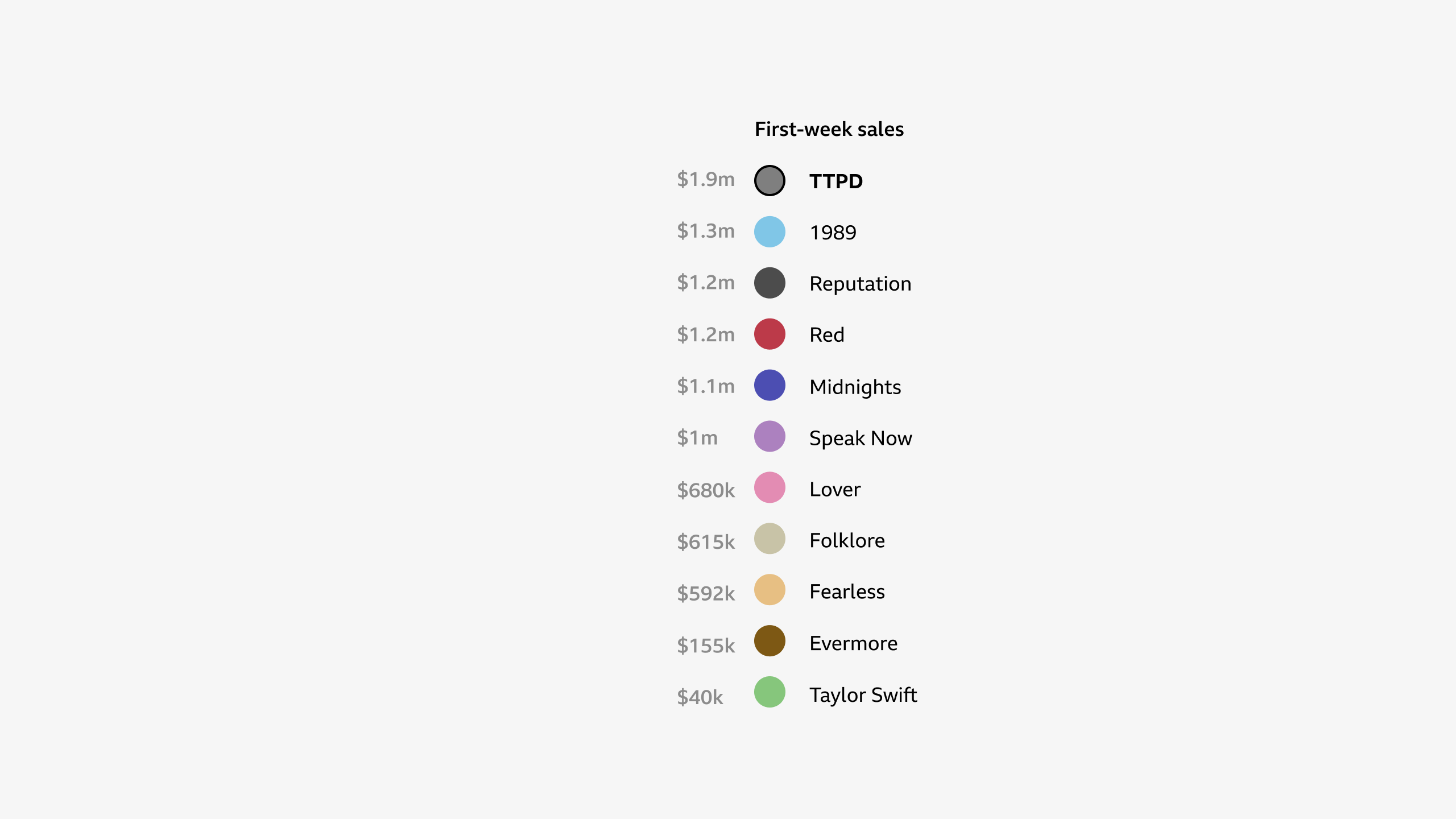

At midnight on 19 April last year, Taylor Swift released her 11th studio album, The Tortured Poets Department.

It was an emotional garage sale. Over 31 tracks of heartbreak and emotional longing, Swift picked at the scabs of her romances with the rock star Matty Healy and actor Joe Alwyn, while pushing back at social media critics and documenting the pressures of fame.

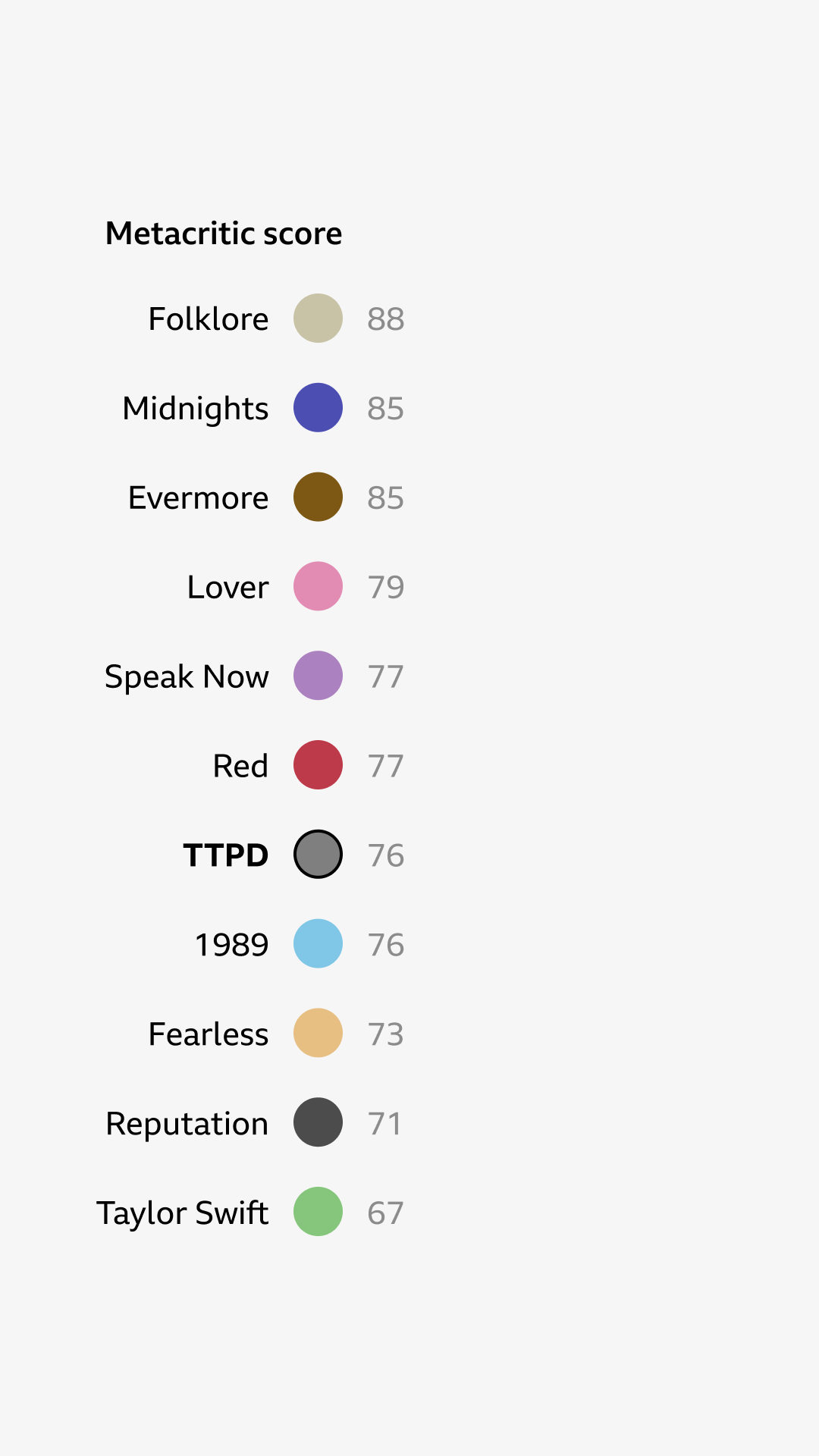

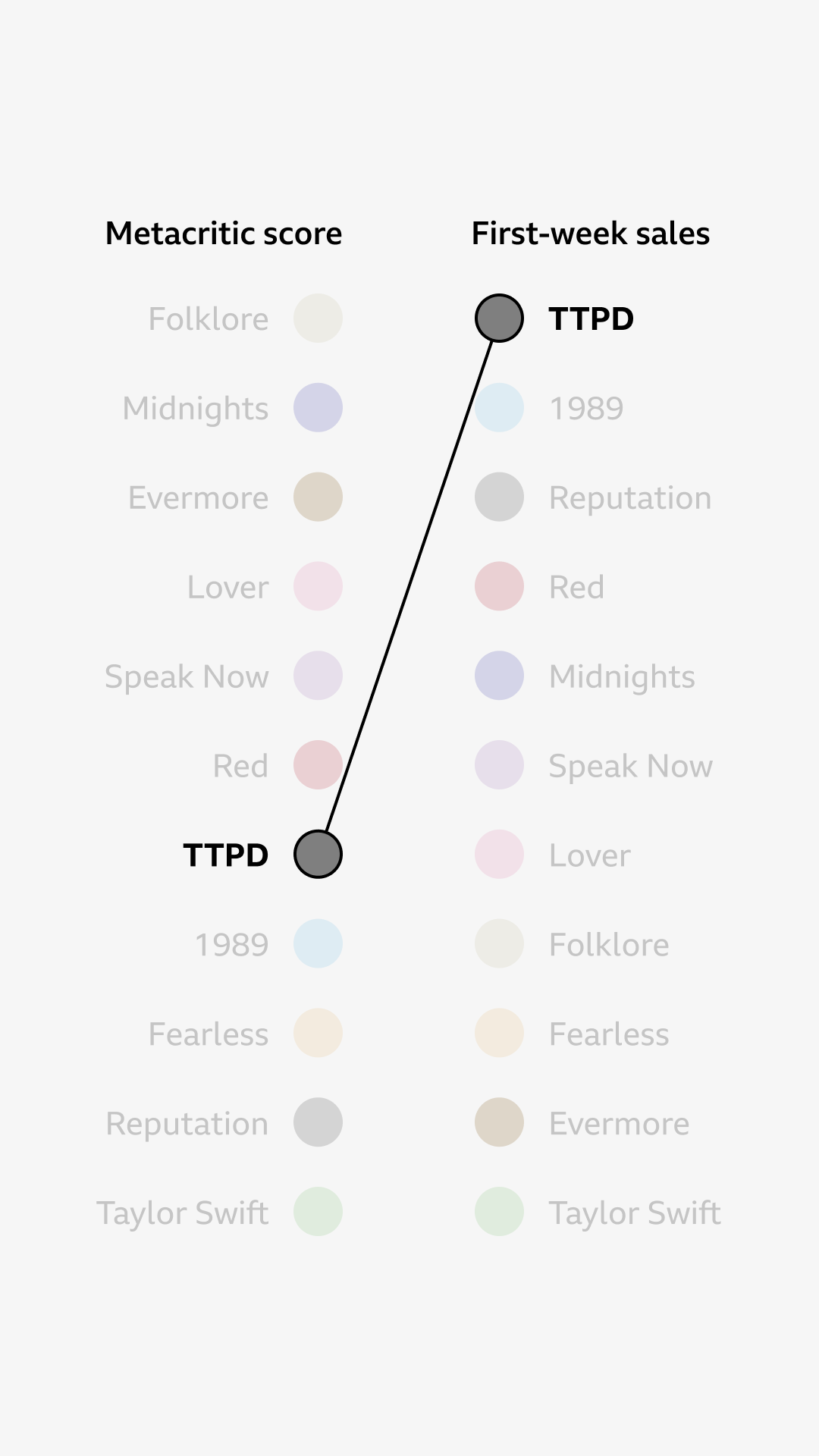

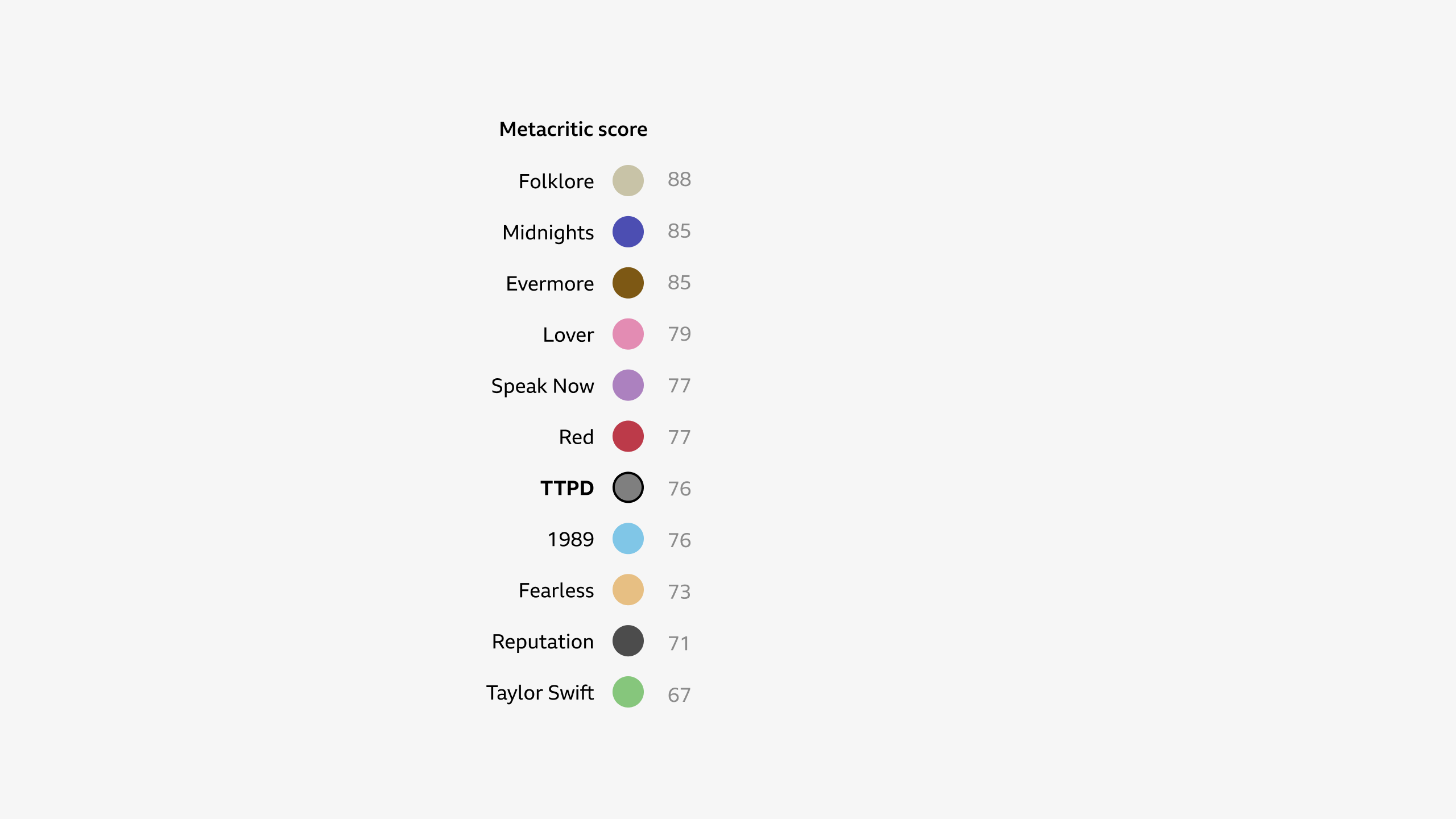

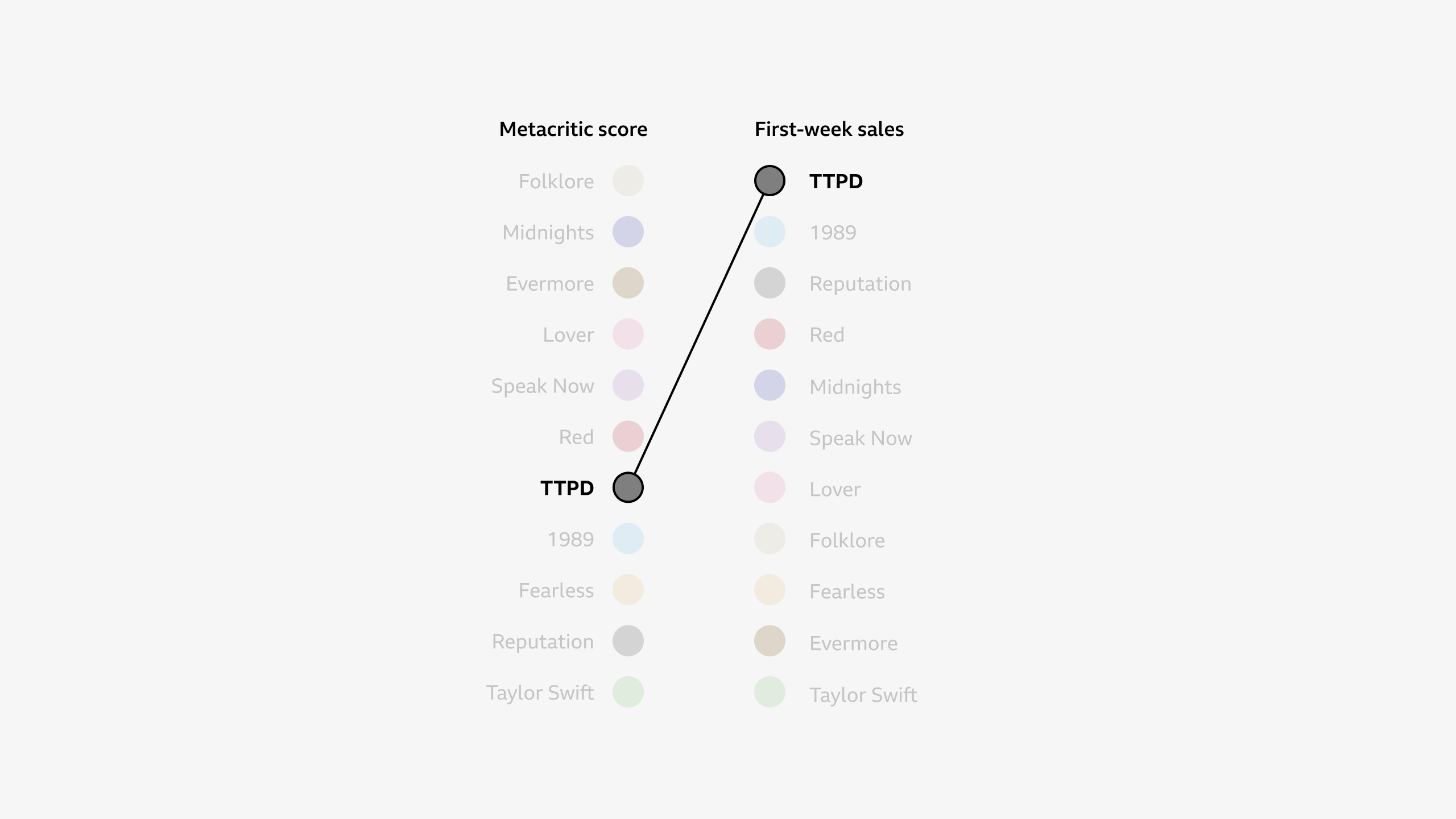

The reviews were middling at best. Music magazine NME suggested it was a “rare misstep” for Swift, with some “cringe-inducing” lyrics. The New York Times described it as “insular” and “self-indulgent”.

My own review bemoaned the lack of editing, calling Swift “prolific to a fault”.

Others were more complimentary - Rolling Stone called the album “gloriously chaotic” - though the response clearly didn’t match the near-universal acclaim of Swift’s earlier work.

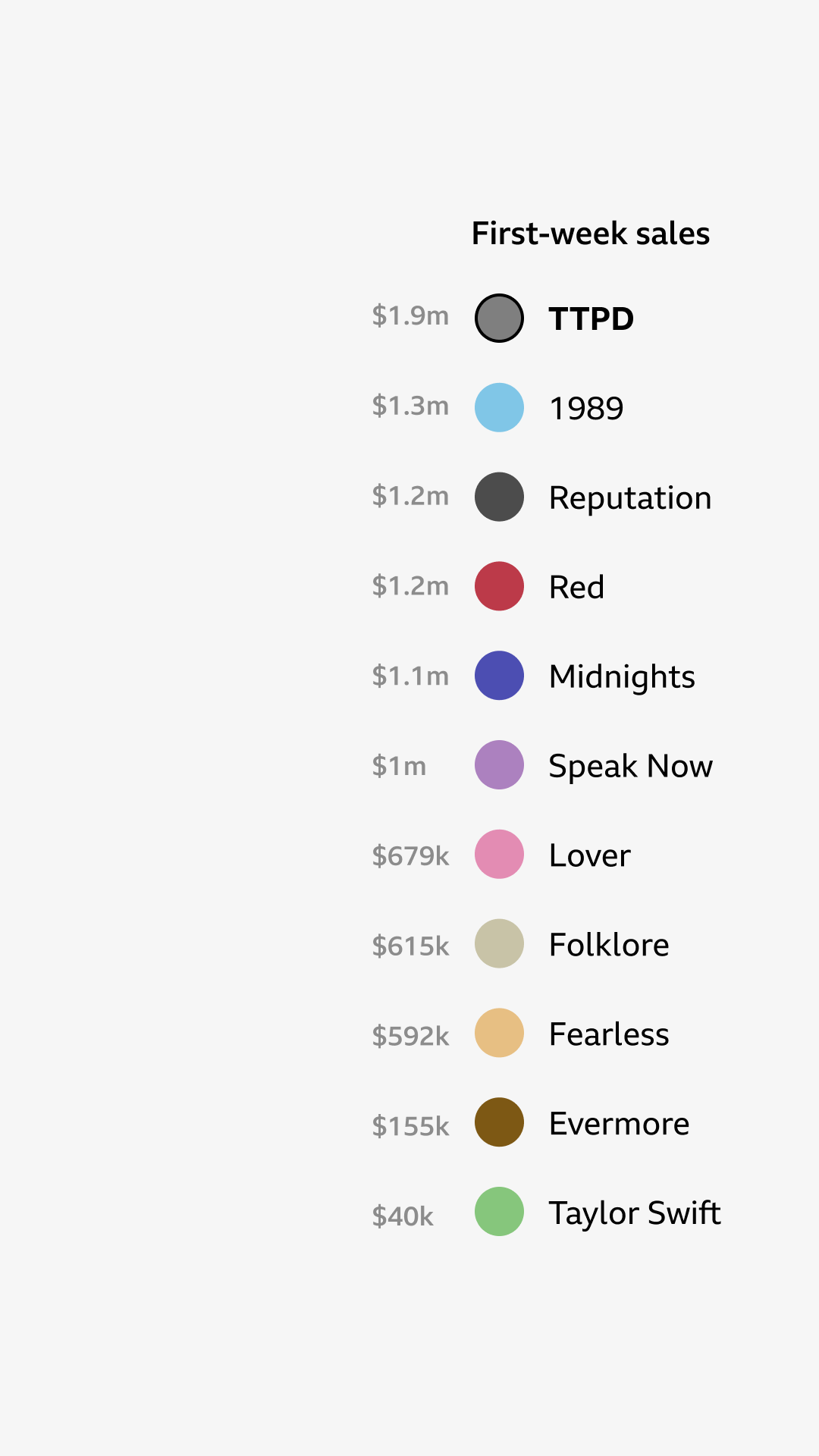

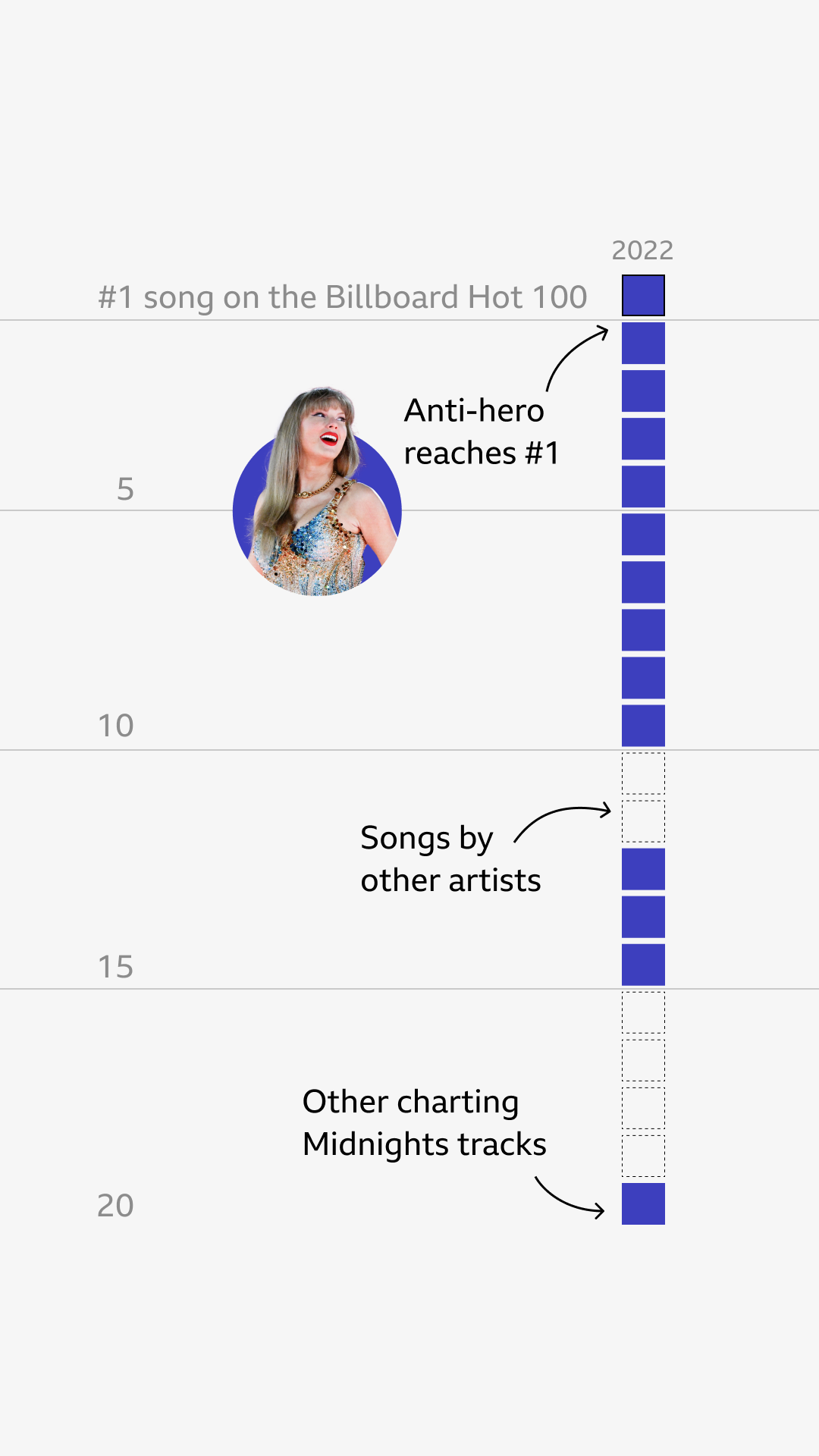

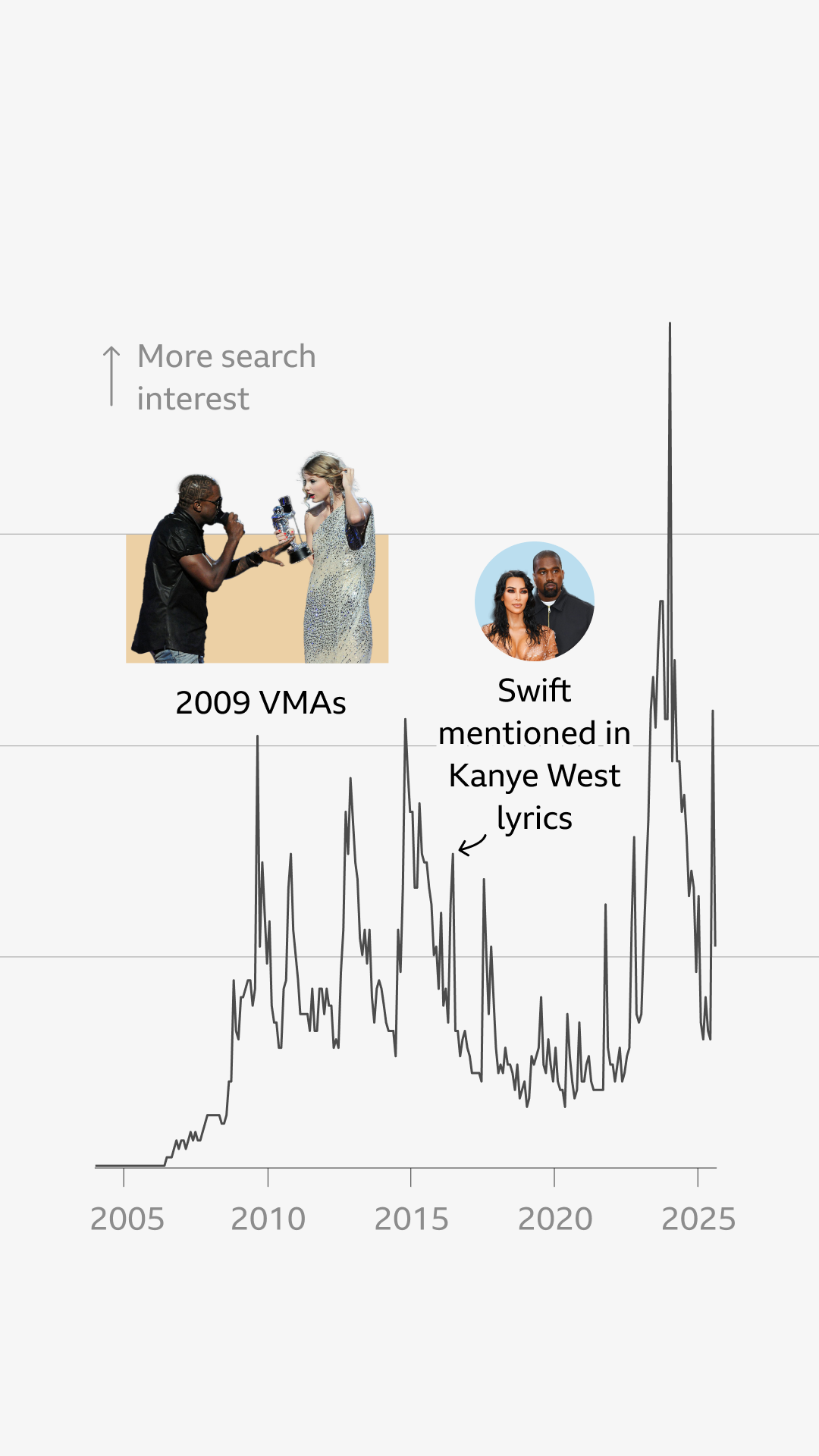

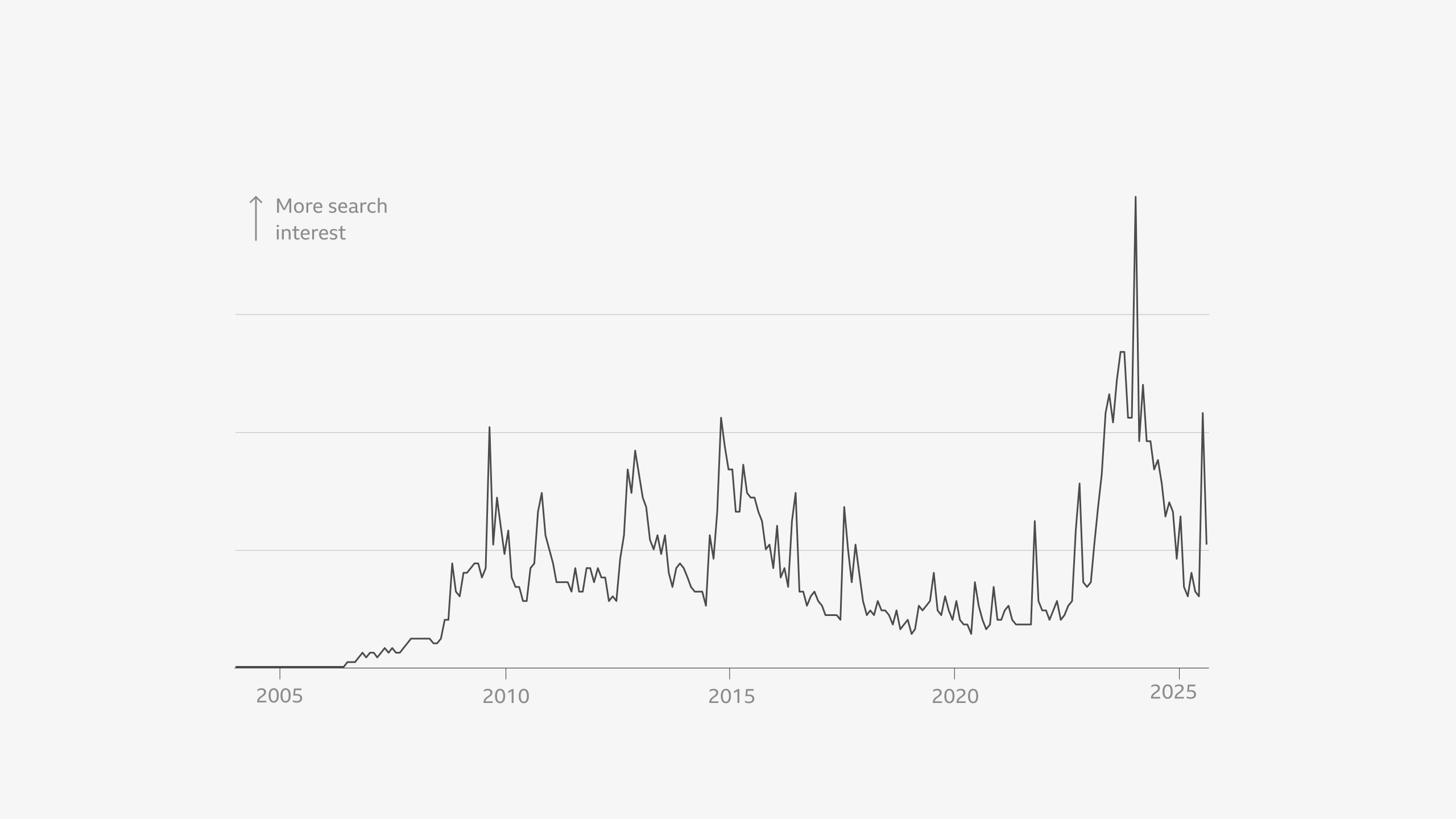

But guess what? Those tepid reviews didn’t matter. Spotify declared it their most-streamed album in a single day. In the UK, it enjoyed the biggest first-week sales in seven years. Right now, it seems nothing can damage Swift.

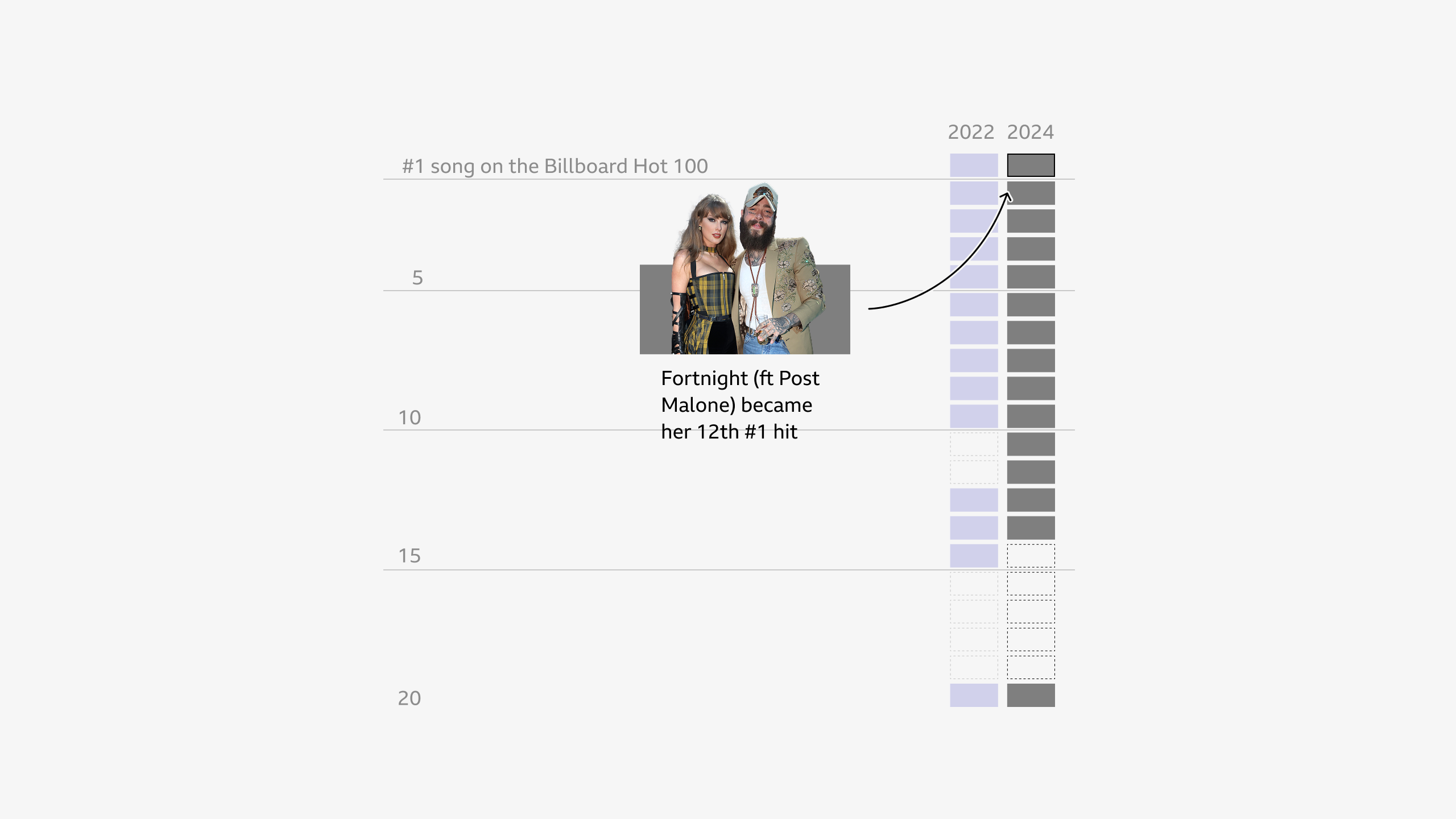

Her newest album, The Life of a Showgirl was released today and already it’s performing phenomenally well, despite mixed reviews. (Though personally, I found it a triumph.)

More than five million fans pre-saved it on Spotify, the largest number in the company’s history, and pre-orders for a special vinyl edition sold out from Swift’s online shop in less than an hour. Hours after its release fans were picking apart the tracks looking for so-called Easter Eggs, and deliberating whether certain lyrics might be referring to Matty Healy, old school friends or other artists (from 50 Cent to Charli XCX).

Swift, at 35, appears to have become too big to fail. Her place as one of the all-time greats is assured. But can her hot streak continue, as public taste shifts towards “messier” singers who are more upfront about their vulnerabilities?

Water-tight image control

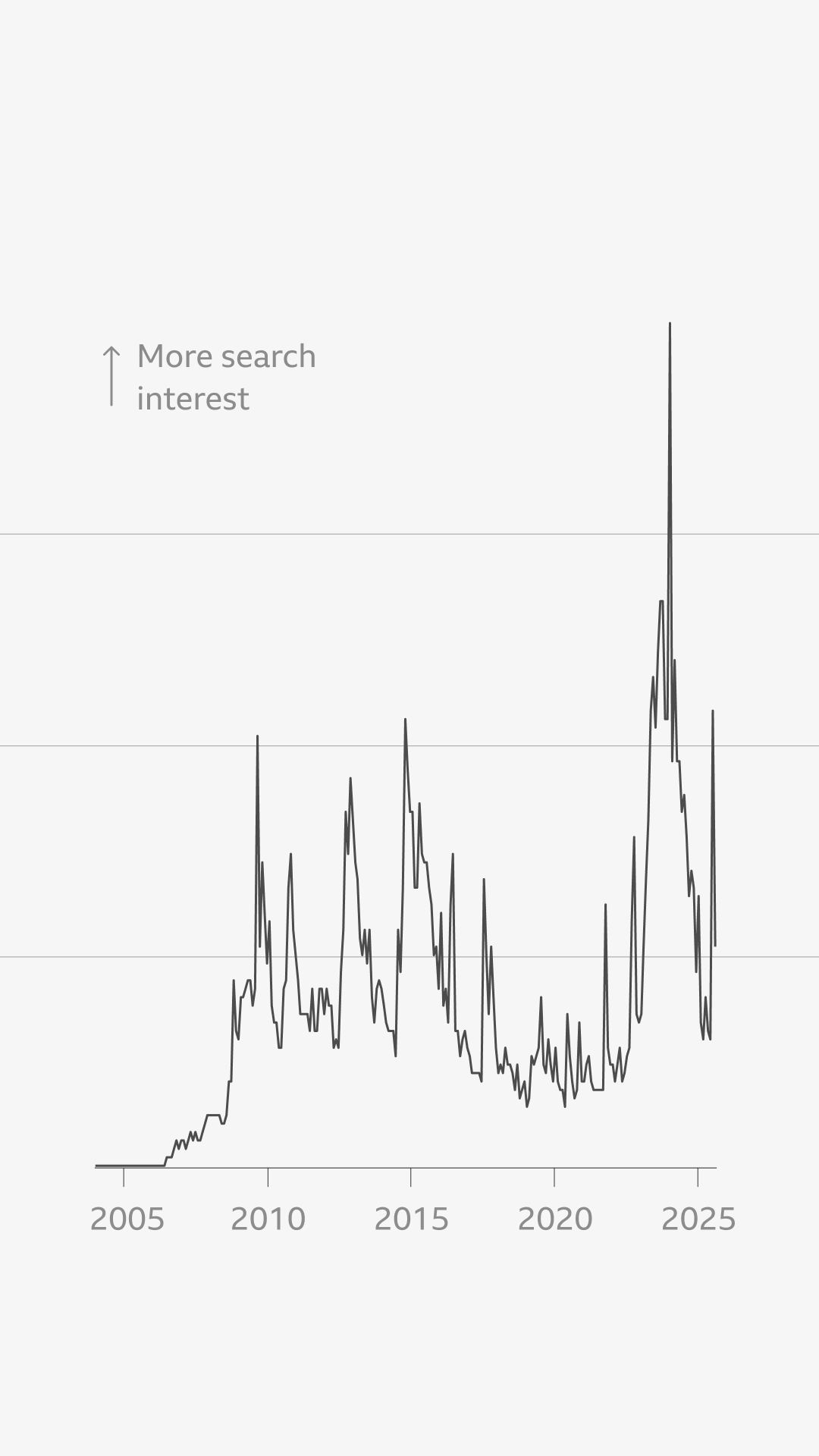

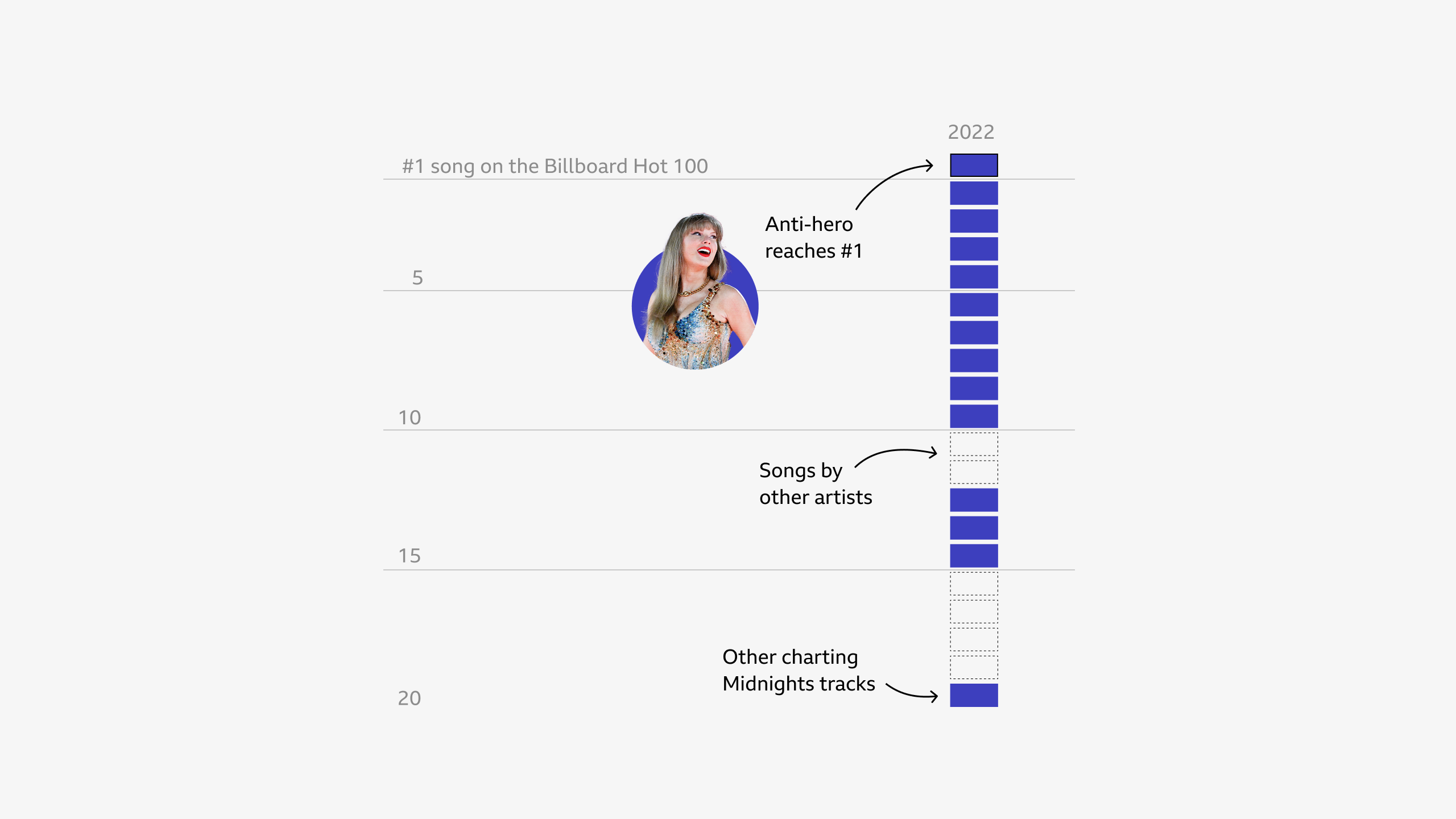

More than perhaps any other current musician, Swift has transcended pop music.

It's not just that she is big - other stars, like Michael Jackson and Madonna sold more records than her (albeit before the streaming era chipped away at sales figures).

What sets Swift apart is that she has escaped the confines of the music industry itself, building her own universe around her.

Through painful negotiation she won ownership over her creative rights, meaning she is not reliant on record labels the way many other artists are.

And she has cultivated an army of ultra-loyal ‘Swifties’ - tens of millions of fans who are almost guaranteed to download her latest release, regardless of what critics say.

“She has built this empire around her where no one can tell her what to do except Taylor herself,” says Tatiana Cirisano, a music analyst at MIDiA consultancy.

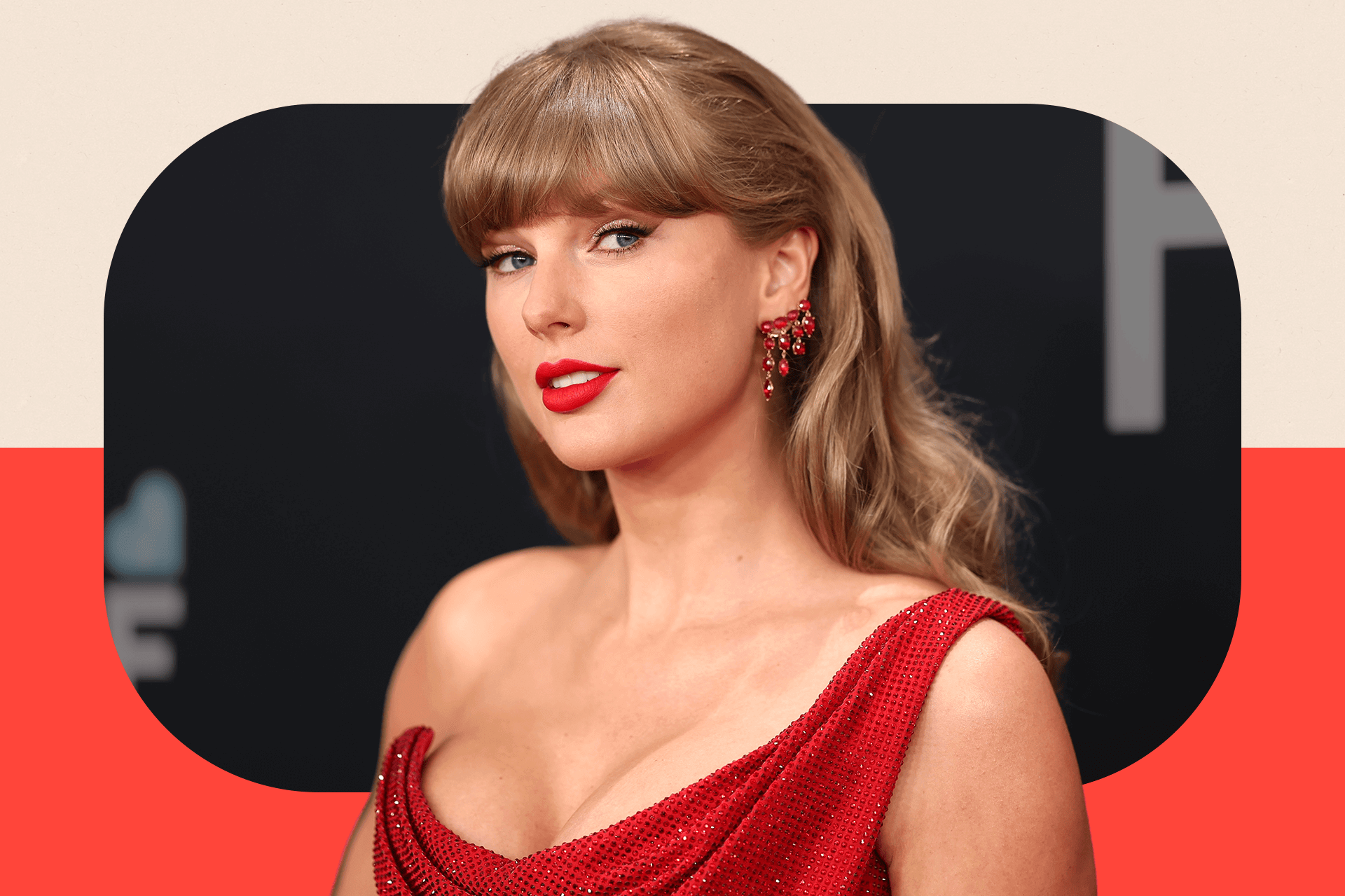

But at the core of Swift’s success is a water-tight control over her public image.

She has not given an in-depth interview to a mainstream magazine since 2023, when she spoke to Time after they named her Person of the Year. It means the only things fans learn about her come directly from her - whether her social media posts or details they glean from her lyrics.

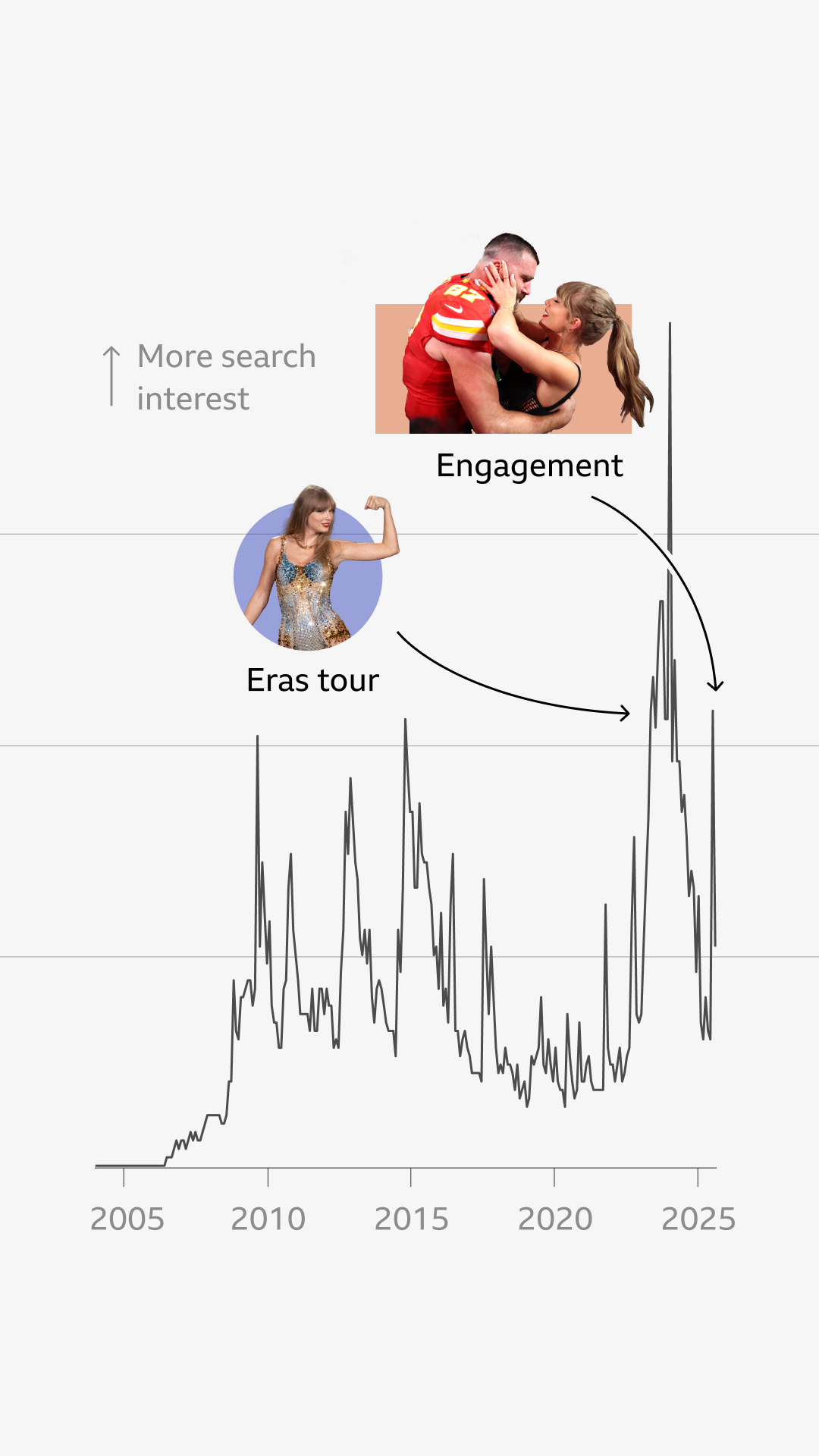

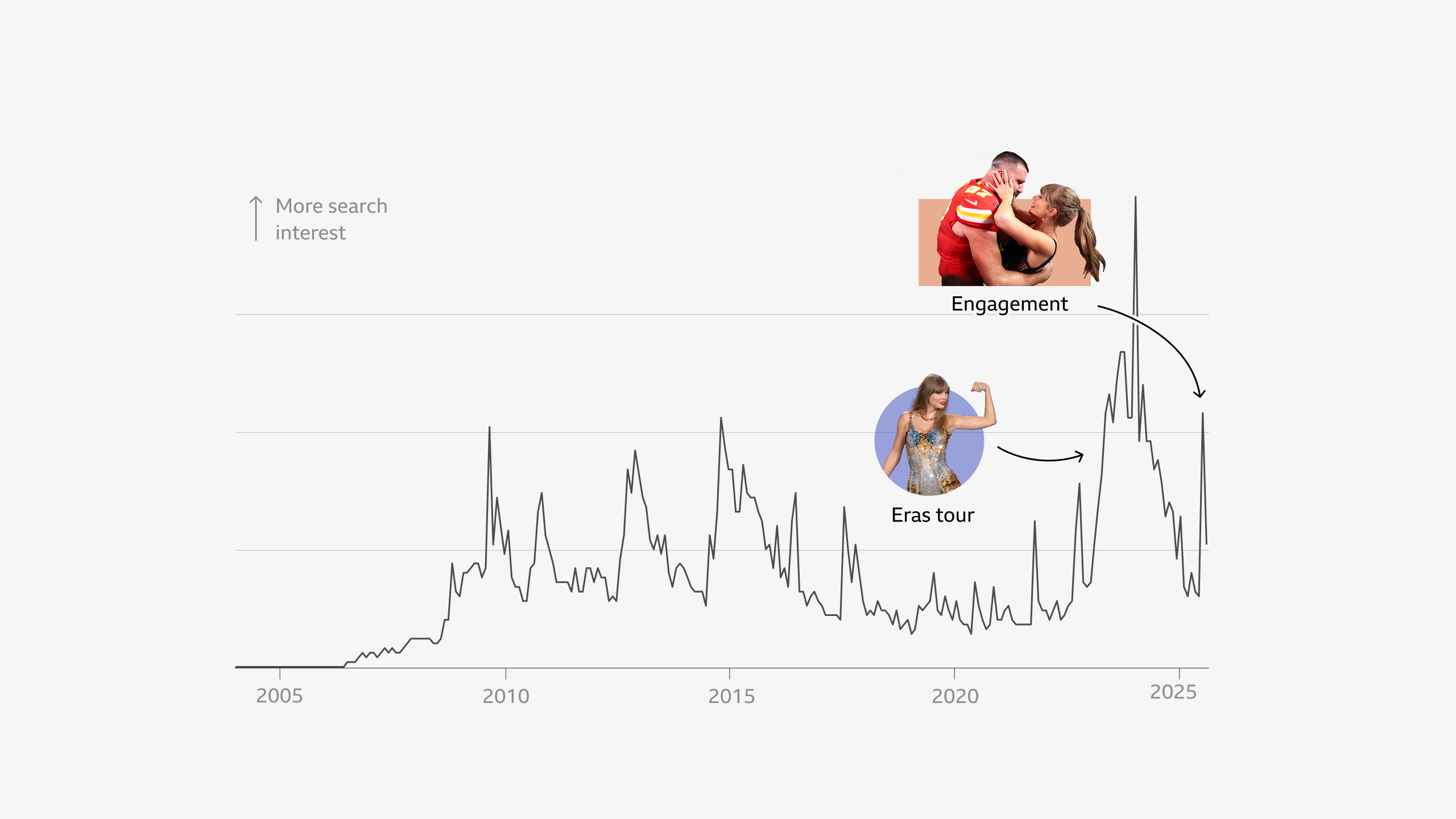

She announced her recent engagement - to American footballer Travis Kelce - on her own Instagram too; and promoted her new album with an appearance on his New Heights podcast, where she presumably had some editorial control.

“It’s very in character for her to be making these announcements directly - not filtered through anyone else,” says Annie Zaleski, a music historian and author of Taylor Swift: The Stories Behind the Songs.

Swift has always valued having a direct pipeline to her fans. Ms Zaleski says it is part of a communications style that dates back to Swift’s days as a teenage country singer in Nashville, when she built an audience on the early social platform MySpace and, later, Tumblr.

“From a very young age, she has cultivated a really accessible online persona.”

Swift may well be following the path set by her friend and contemporary Beyoncé, who in the 2010s largely removed herself from the media and asserted control over her own image, through meticulously-planned album campaigns and documentaries that construct her mythology.

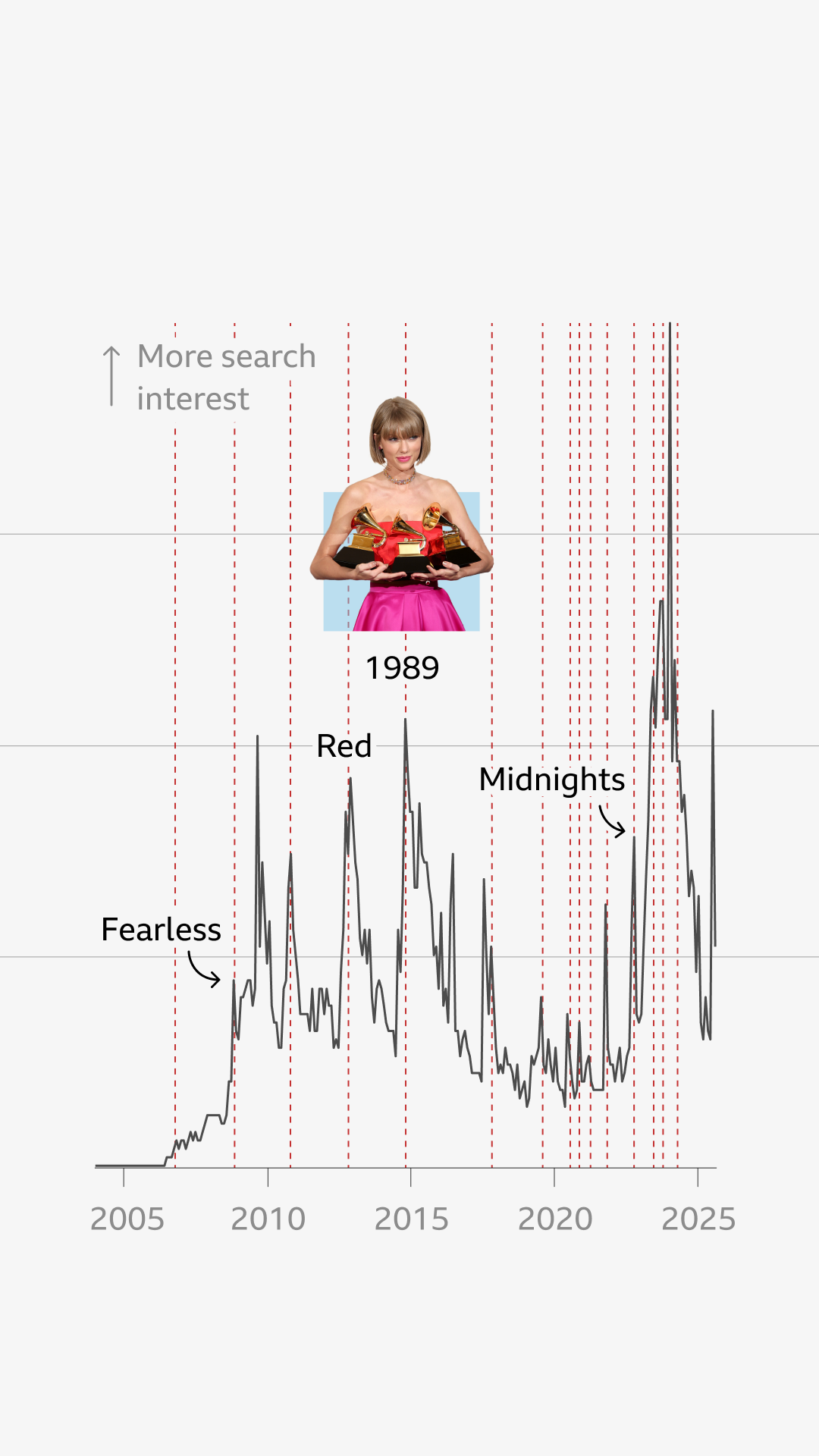

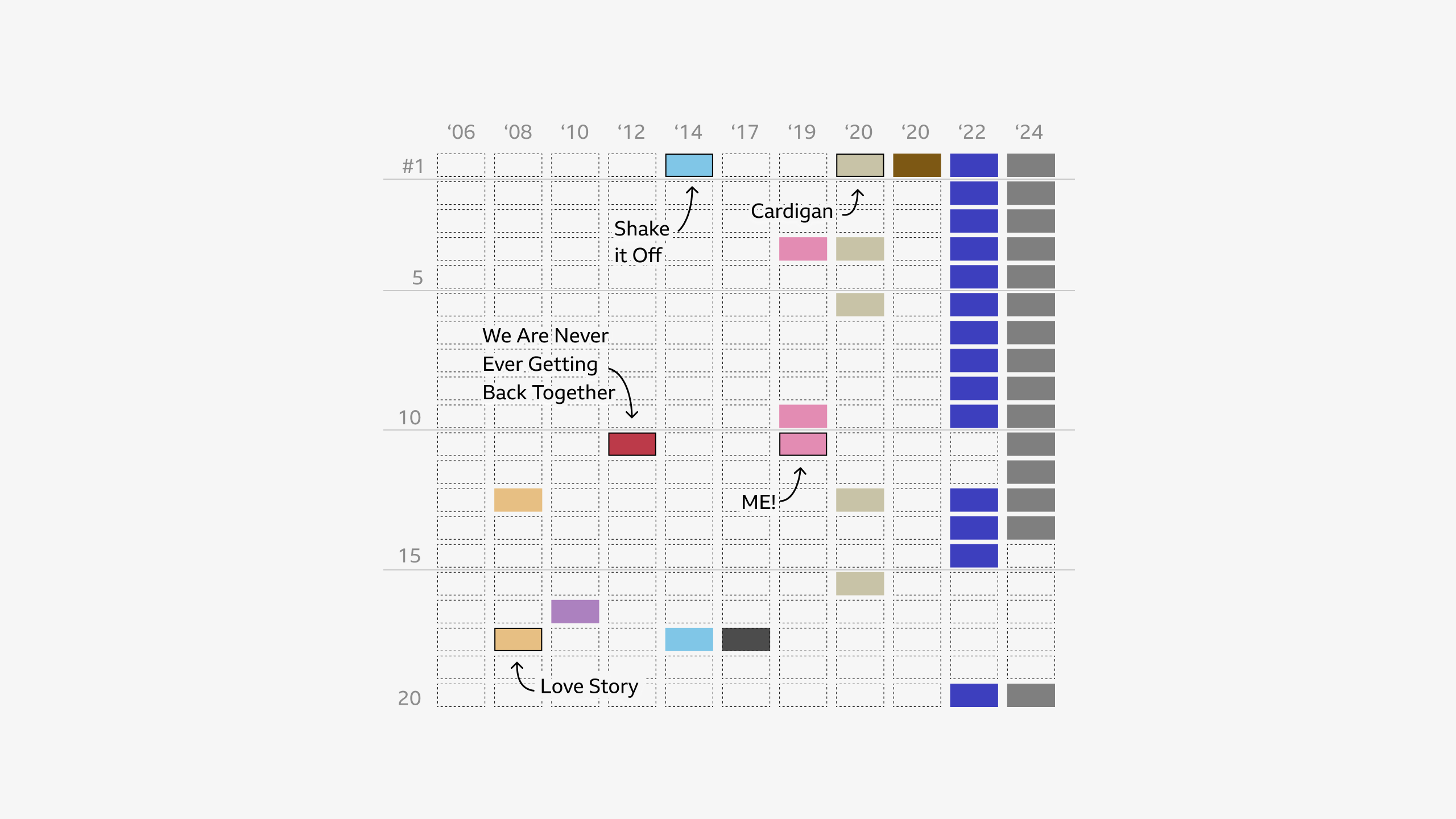

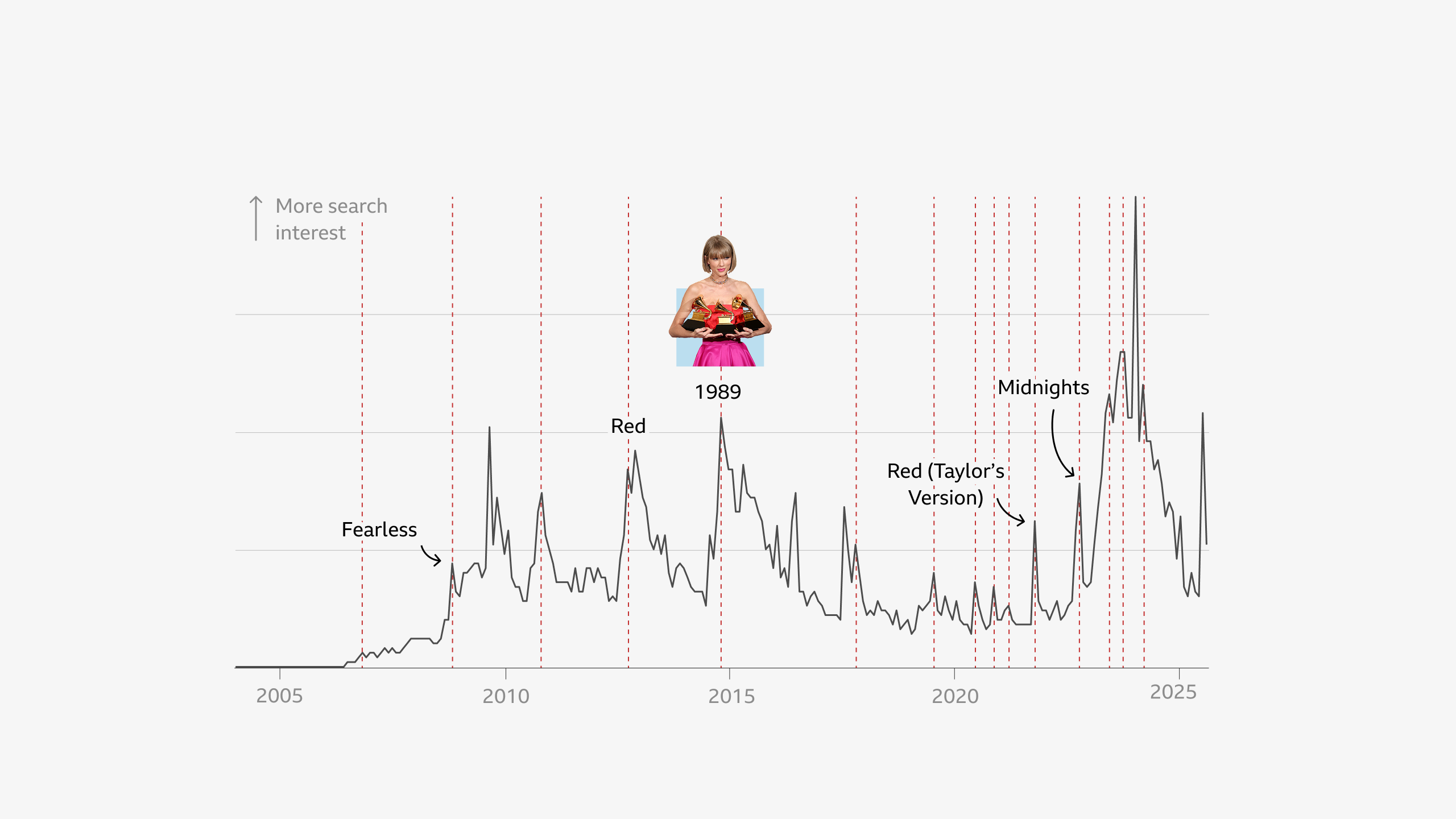

With each new album (or era) Swift successfully focused on reinventing herself: from country music, to innocent love songs about crushes and fairy tales, to the electronic pop-rock Taylor of the early 2010s, via her folk music, and now into the modern era, in which she combines synth-pop with songs about revenge and power ballads.

Not quite ‘David and Goliath’

Swift has also taken control of her music rights - something that’s still surprisingly uncommon.

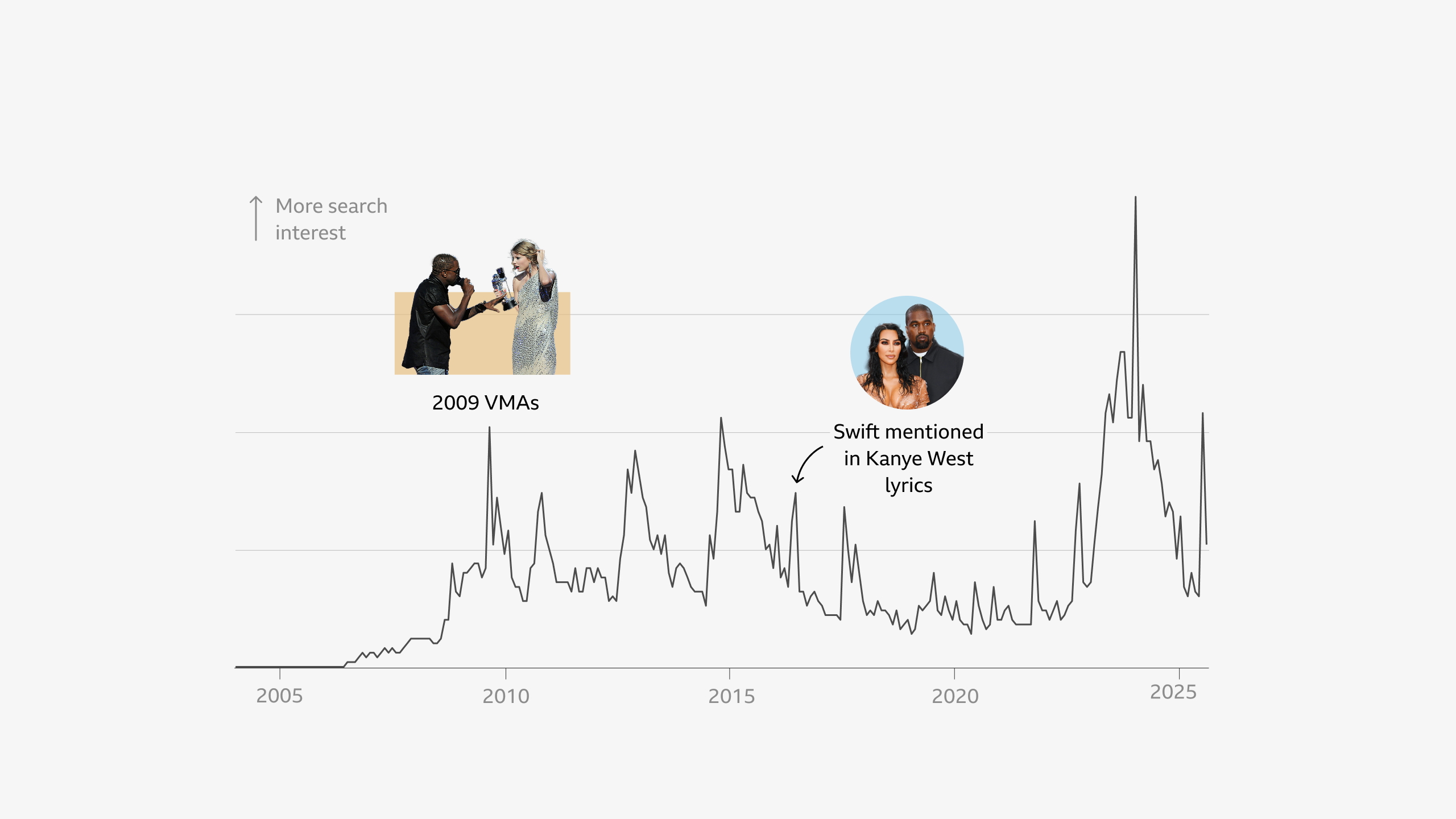

In 2019 she publicly fell out with her old label, Big Machine Records, after they sold the rights to her first six albums to the music manager Scooter Braun, a man she accused of bullying. Braun denied the allegations.

She then decided to re-record her first six albums under the title ‘Taylor’s Version’ - essentially superseding the originals.

This relied on a quirk in music law: whilst her old record company had the master’s rights to the albums (meaning they owned specific recordings of each song), she retained the publishing rights to the melody and lyrics.

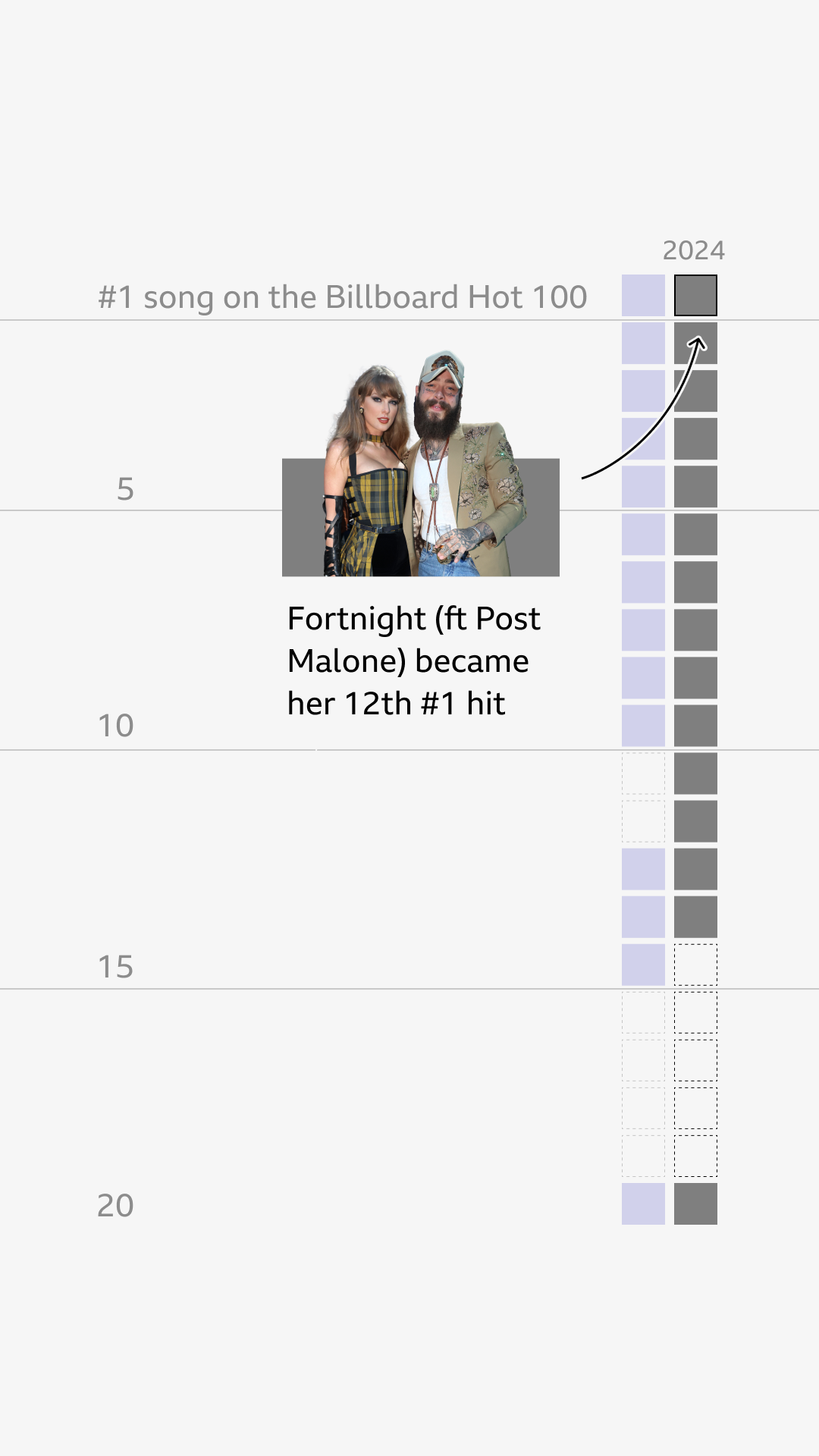

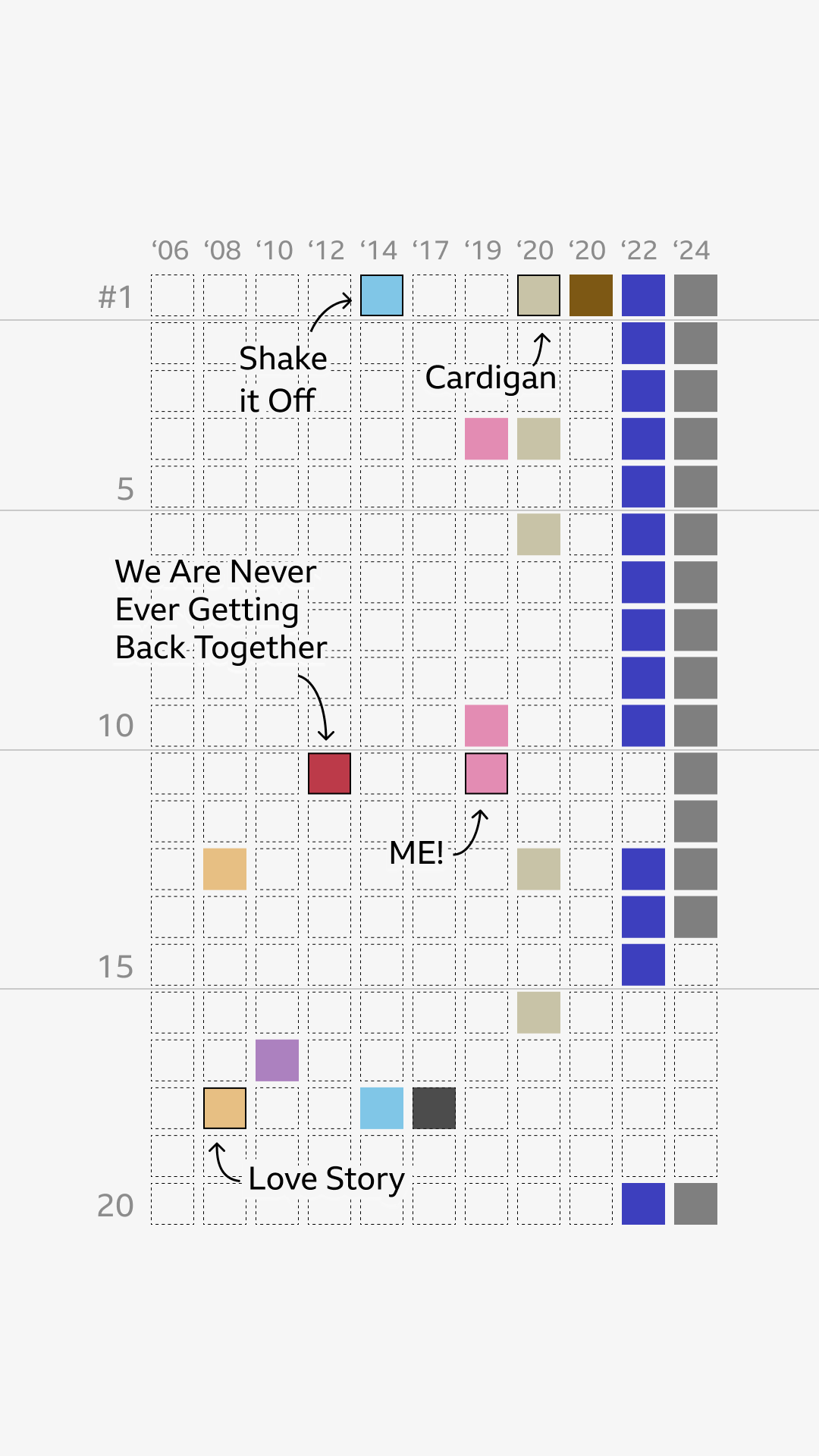

It meant she could refuse permission to radio stations and TV shows that wanted to play a snippet of Shake It Off or Love Story - unless they played the new version that she controlled.

And when signing her new contract with a record label in 2019, Swift insisted on both the master’s and publishing rights - meaning in effect she now has total ownership over when and how her music is played.

For Annie Zaleski, this willingness to take on the music industry sets Swift apart. “It’s very rare to have all of those rights in one place.”

In May this year Swift completed the saga by buying back her master’s rights from her old record company. “All of the music I've ever made now belongs to me,” Swift wrote on her website. “I've been bursting into tears of joy.”

It was a tortuously public process - and that’s partly why it was important, argues Ms Zaleski. “I absolutely love that she demystifies so many complicated business dealings.”

It also changed the story for other artists. Swedish pop star Zara Larsson told me how, when her record label was put up for sale, its chief executive offered her the chance to buy her master recordings.

“[He] saw what went down with Taylor [Swift] and felt that would be his nightmare.”

Not everyone is as impressed by Swift’s business dealings.

Eamonn Forde, an author and music industry commentator, says it’s easy to paint a simplistic “David [versus] Goliath” narrative about the star’s battle with her record company. Instead he believes there may have been an element of “peevishness” at play in her decision to re-record her old albums.

Negotiations in the music industry are, he says, “obviously driven by money, but also by ego… it was a curious cocktail of all of those things underpinning it, I think”.

And he points out that Swift is not the first musician to seek control; other stars including Paul McCartney, he says, went to court over the publishing rights to their music.

How multi-generational Swifties ‘insulate her’

Swift has built such a dominant role as the queen of pop, few have asked how and when she might be dethroned. Now though, questions are quietly being mooted.

First, there is her impending marriage. Swift has made a fortune writing about heartache and unrequited love - so when the 14-time Grammy winner announced her engagement, some wondered where that might leave fans who connected with those heartbreak lyrics.

“Now that Swift is entering her bridal era, is this the end of vast swathes of relatable heartbreak songs that have sound-tracked the lives of her fans?” asked ABC News.

But the analysts we spoke to pointed out that so-called Swifties now span many generations - from long-term fans who first noticed her as a country music singer back in 2006, through to the teenagers at her Eras Tour. “That really insulates her,” says Ms Zaleski.

Her lyrics have evolved since her early albums too.

“She has much more depth as a songwriter than a lot of people realise - and that helps her stay resonant,” Ms Zaleski argues.

She is also helped by her ability to shape shift - from her country era in the 2000s to her transition to pop and her “squad” friendships with famous singers and supermodels including Karlie Kloss, Selena Gomez, Cara Delevingne and Gigi Hadid.

Her career arc most clearly resembles Madonna, who reinvented herself a number of times. But Swift also knows that no one – not even Madonna – can dictate pop culture forever.

‘People want to get dirty again’

The most precarious problem for Swift – for any pop star, really – is when musical tastes change and you’re left in the wake.

Right now, a new generation of female singers are shunning the polished perfection of Swift’s music, revelling instead in imperfection and uncertainty.

Ms Cirisano suggests that there is a new mood of apathy and nihilism - one that British singer Charli XCX successfully tapped into with last year’s album Brat, which she described as “chaos and emotional turmoil set to a club soundtrack”.

“It fit perfectly with that post-pandemic [sense of] people want to get dirty again, they want to smoke, they want to party and get people’s sweat all over them,” says Ms Cirisano. “This feeling of nothing matters.”

Take Olivia Rodrigo, 22, who writes about meeting up with her ex-boyfriends even though she knows it’s a bad idea. Or Lola Young, 24, who sings in her track, Messy: “I smoke like a chimney… and I pull a Britney every other week.”

Swift, who turns 36 in December, doesn’t quite fit this mould. She has always more closely resembled an all-American prom queen. Yes, she has admitted to imperfections on some albums - but whether she’s singing about romantic entanglements, or celebrity disputes, Swift often emerges with the upper hand.

“Does Taylor’s aesthetic and vibe mesh with what’s going on in the culture right now?” asks Ms Cirisano. “We’ll have to see.”

The bigger the height, the greater the fall

Yet she also suggests that the sheer scale of Swift’s success could ultimately be her undoing. “The bigger you get, the more people question how you got there and do you deserve it?”

Some environmentally-minded critics have questioned Swift - whose personal wealth stands at about $1.6bn (£1.2bn), according to Forbes - for flying by private jet. She has also come under fire for her marketing partnership, through which some customers of the bank Capital One got earlier access to tickets.

Journalist and Swift fan, Shannon Palus, wrote that the Eras Tour had unveiled “the least fun version of Swift yet: Capitalist Taylor,” in an article for Slate magazine in 2022. She complained that after hours waiting in an online queue, the only option was a special package costing $755 (£562).

“It’s the fans she’s extracting money from, and for some of us, being asked to pay hundreds of dollars to see her live… feels disorienting,” she wrote.

Last year she was criticised by some for taking too long to pick a side in the US presidential election.

When she did endorse Democrat Kamala Harris, she took flak from Republicans - including Donald Trump himself, who wrote on his Truth Social platform: “I HATE TAYLOR SWIFT!”

The criticism from so many angles is an inevitable symptom of Swift’s unparalleled success, says Ms Cirisano.

“The crown wears heavy on the head. The bigger you get, the more eyes [are] on you.”

But analysts agree that her decline, if it ever comes, is many years away. And The Life of a Showgirl will almost certainly break new records.

For now, at least, we’re living in Taylor Swift's universe.

Data sources

Billboard, Metacritic and Google Trends

Media credit

Getty, Taylor Swift via Instagram/Reuters, TAS Rights Management